ENCONTROS COM PATAÑJALI YOGA SŪTRAS:

RĀGA, DVEṢA E ABHINIVEŚA

Coordenação: Marcia Neves Pinto

Dando continuidade ao tema dos kleśas (aflições), lê-se no Yoga Sūtras de Patañjali que o prazer conduz ao desejo e ao apego emocional, o que gera cobiça e luxúria (II.7 – sukha anuśayī rāgaḥ): a pessoa se torna absorvida pela busca do prazer e viciada na gratificação dos sentidos, permitindo-se enredar no sofrimento e na doença.

Rāga vem depois de asmitā nos Yoga Sūtras (que estabelece a ordem de importância dos tópicos em ordem decrescente, como os demais textos hinduístas) porque somente após o sentimento de “eu” é possível haver um sentimento de “meu”, que é nascido do desejo e apego a várias coisas/pessoas.

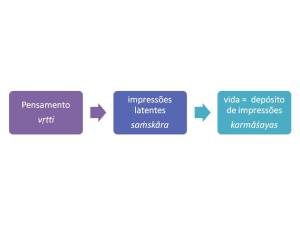

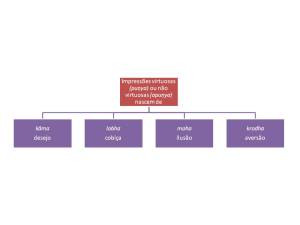

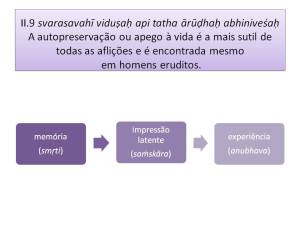

A conexão entre rāga (desejo) e smṛti (memória) se dá em função de que a lembrança (saṁskāra = impressão latente) de um prazer é essencial ao nascimento do desejo de experimentar aquela sensação novamente. Na falta da memória temos a inabilidade de lembrar da experiência. Por isso Bryant[1] afirma que o ingrediente chave do apego (rāga) é a memória. Quando um novo modo de prazer é similar ou igual a um prazer já experimentado no passado, a memória infere a promessa de prover prazer novamente no presente ou no futuro. Portanto, a memória precede ao apego e pode mesmo conter impressões latentes de vidas anteriores, saṁskāras.

Ignorância e o sentimento da individualidade do ego fazem com que a mente iludida associe esses saṁskāras ao eu, identificando-o com os sentidos através dos quais esses impulsos latentes direcionados ao prazer podem se expressar. Esses kleśas fazem com a mente identifique o eu com o não-eu, isto é, corpo e mente.

O problema com ter desejos e apegos é que eles causam os vṛttis, as perturbações na mente. Mais que isso: as impressões latentes (saṁskāras) que eles causam, provocam a instabilidade atual e futura da mente (II.15). Satisfazer um desejo não faz com que nos livremos dele, ao contrário, faz com que desejemos repetir a sensação de prazer, assim tornando-o mais agudo.

Hariharananda (cf. Bryant) observa que, quando o desejo se aprofunda em cobiça, o sentido de certo e errado, moralidade e ética, são negligenciados. Quanto maior a cobiça, mais provável se torna que a pessoa faça uso de meios imorais para obter os objetos desejados.

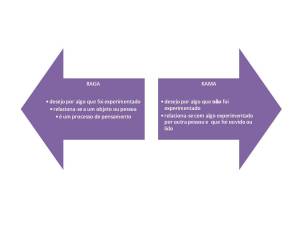

A diferença entre rāga e kama é:

Por outro lado, dor, sofrimento e miséria engatilham a cadeia do ódio ou aversão (II.8 – duḥkha anuśayī dveṣaḥ, a infelicidade conduz ao ódio). Recolhendo prazeres perdidos, atormentado pelos desejos não preenchidos, o homem é levado ao sofrimento. Em extremo estresse, ele começa a detestar a si mesmo, à sua família, aos seus vizinhos e cercanias, sentindo uma sensação de inutilidade. De modo similar ao apego, a aversão, seu exato oposto, tem na memória sua causa.

A aversão (dveṣa) se relaciona com a violência (hiṁsa) na medida em que dá origem à raiva, que acarreta na retaliação, cuja expressão é a violência nas palavras ou nos atos. E desde que não podemos prever a reação à nossa retaliação, mais violência pode ser gerada.

Ademais, é mais difícil se livrar da aversão do que do desejo, porque um desejo pode ser substituído por outro. Já a aversão é direcionada a uma coisa ou pessoa definida, baseada no medo ou mágoa que aquilo causou.

Não há uma maneira de nos livramos do desejo e da aversão, visto serem emoções fundamentais e até imprescindíveis à sobrevivência. O que podemos fazer é entender suas conexões, minorar sua intensidade e o efeito que podem ter sobre nossas escolhas, ações, vidas, através da prática de kriyā yoga, detalhada nos Yoga Sūtras.

Uma pessoa discriminativa luta por adquirir conhecimento de modo a alcançar equilíbrio entre sukha e duḥkha e a viver independentemente das sensações de prazer ou dor.

Passamos, então, à abhiniveśa, ou medo da morte/apego à vida, que é um medo que está profundamente enraizado em todos os seres vivos, do sábio ao ignorante, espalhado em todas as nossas células, que engloba o medo de perder o que se possui, o medo da dor e o medo do desconhecido. Todos os seres vivos nascem com o desejo de viver eternamente. E isto é motivo de sofrimento (duḥkha):

II.9 svarasavahī viduṣaḥ api tatha ārūḍhaḥ abhiniveśaḥ

“A autopreservação ou apego à vida é a mais sutil de todas as aflições e

é encontrada mesmo em homens eruditos.”

Com essa afirmação, Patañjali indica que cada ser humano teve um gosto de morte cuja marca impressa é a semente do medo. Este desejo tem origem na memória de vidas passadas, não há outra explicação lógica, tendo em vista que de outro modo não teríamos origem para esse sentimento:

E esse medo da morte/apego à vida que caracteriza abhiniveśa é diferente do desejo (rāga) ou aversão (dveṣa) porque (1) não está fundamentado em uma percepção direta ou inferência desta vida, (2) porque não há relação de causa e efeito para este sentimento nesta vida, donde o que logicamente podemos inferir é que trazemos esse sentimento, essa impressão latente (saṁskāra), de uma experiência vivida anteriormente, de uma percepção direta vivida em uma vida anterior.

E porque esse sentimento tem origem na experiência de morte havida anteriormente, ele é comum tanto ao sábio quanto ao ignorante, também por isso é que o simples estudo das escrituras não removerá abhiniveśa, a menos que a pessoa, por meio da prática profunda do yoga, alcance o raro estado de samādhi, em que finalmente percebe que não é o corpo, mas a alma perene, imutável, imortal, o Self (o Si-mesmo).

O praticante de āsana, prāṅāyāma e dhyāna, penetra profundamente em si mesmo e experimenta a unidade com o fluxo da inteligência e a corrente da sua própria energia. Nesse estado ele percebe que não há diferença entre a vida e a morte, que elas são, simplesmente, os dois lados de uma mesma moeda.

Abhiniveśa é uma imperfeição instintiva, que pode ser transformada em conhecimento instintivo, por meio da prática de yoga. Através desse entendimento perde-se o apego à vida e aniquila-se o medo da morte, libertando-se das aflições e sofrimentos, de consequência conduzindo-se em direção a kaivalya.

O medo da morte sugere que esta experiência já foi vivida e que está estocada na memória de uma forma não prazerosa. E, sugere Balsev (cf. Bryant), talvez porque o apego à vida/medo da morte seja um saṁskārapertencente a uma vida passada e não à presente, seja o motivo pelo qual este kleśa está em um sūtraseparado das demais formas de apego/aversão.

Este saṁskāra parece ser o argumento mais antigo oferecido pelos hindus na defesa da existência e imortalidade da alma.

Ações baseadas em avidyā e demais kleśas deixam suas respectivas impressões/marcas (karmāśayas), que podem ser vivenciadas na vida presente ou em uma vida futura. Deste modo, nossas ações determinam nosso futuro, nosso karma.

E os frutos da ação estão relacionados à intensidade da busca.

Em suma:

Namāskar!

[1] Edwin F. Bryant, The Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, 2009, North Point Press, New York, USA.

Você precisa fazer login para comentar.