5. The integration of the other limbs of the eight-limbed path into Asana

Part II: Detailed Analysis: The Hidden Presence of Astanga Yoga in Asana

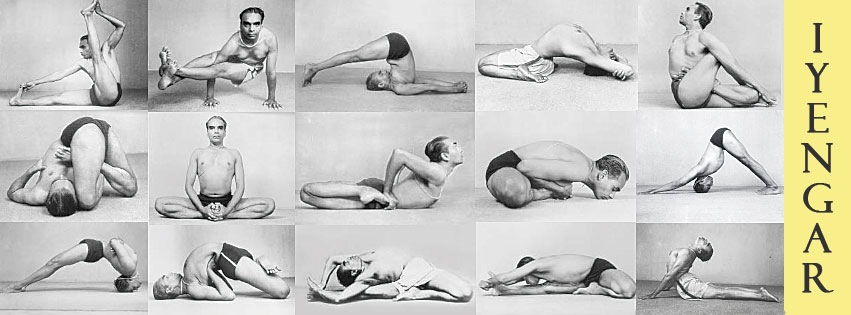

The problem from which my thoughts about Iyengar`s reference to the Yoga tradition proceed can be expressed in the following manner: Every mindful reader of “Light on Yoga” will ask what the relation is between the comparatively brief introductory part dealing with traditional Yoga philosophy and the very voluminous description of the various Asanas which follows. The book itself does not give a satisfactory answer. There is a gap between the two parts and this gap is the yet unbridged difference between the tradition and Iyengar´s own approach to Yoga.

Iyengar is aware of the limitations of his first major work in this respect ( Analogous problems reappear in “Light on Pranayama”). In a conversation with Neela Karnik he gave as the main reason for writing “Light on Yoga” his wish to convince the public of his authenticity and earnestness by completely documenting his Asanas. He remarks that in those days, he had not been able to present the essence of his art, that is the process of personal growth and self-realisation initiated by the struggle for precision in the poses, in a sufficiently clear manner. However, it has always been implicit in his practise and in his teaching: “The Asanas came because I followed the principles of Yama and Niyama. I involved my entire self – physical, emotional and intellectual. The entire body becomes a basis for meditation. Each pose is meditation. The body is a temple. The ´atma´ needs a clean place to live. That is why the book shows a detailed technique. But Yama-Niyama has to be understood. The book has limitations. But my pupils have to realise this. When I am teaching you, you realise your involvement and your own ´culturing´. You are evolving emotionally, intellectually, spiritually. Now this could not be put in the book – it is implicit in my technique.” [28]

In “The Tree of Yoga” Iyengar takes an important step in the direction of an original “Iyengar Yoga philosophy”, which integrates the old Yoga by trying to illustrate and explain the implications of his practise of Asana using Patanjali´s eightlimbed path as a conceptual framework. The following interpretation is based mainly on the second part of this book.

5.1 Yama in Asana [29]

In “The Tree of Yoga” Iyengar sticks to the view taken in the passages already quoted concerning Yama and Niyama.[30] As earlier in “Light on Yoga” he describes Yama as the root from which all Yoga grows. But now he shows which place Yama takes in the practise of Asana itself, how it is present when we work on the pose. More deeply and in more detail than ever before he develops the connection of Yama with the basic principle of Asana: the proper extension of the entire body.

This extension means Ahimsa, because it avoids the violent forms of over- and under-extension which lead to injurious strain on the one hand and on the other hand to slackness, which is just as destructive because functions not being used waste away and finally die.

Satya, truth in the exercise of the body, according to Iyengar, is gained insofar as the single stretch which moves the whole body, reveals the reality of our embodied being. The weak points are not avoided but integrated into the exercise. Slumbering points are awakened and the openness of our bodily existence increases.

Practise of this kind leads to Brahmacharya, continence in the sense of development of inner energy.[31] The mind stops wandering around; stops being driven by different wants and desires. The energy is not wasted but on the contrary circulating inside the body without loss.

The opening of a complete stretch also liberates from greed and the attitude of grasping and holding on to things. In this way Asteya and Aparigraha (non-stealing and freedom from greed) are integrated into Asana to some degree.

5.2 Niyama in Asana [32]

Practising Asana means a purification (Sauca) of our embodied being: Our capacity for mobility is regained, as is upright posture and unrestrained movement. This leads to satisfacton and feeling comfortable with oneself (Samtosa).

The following principles of Niyama are more demanding and presuppose more experience and understanding.

Tapas: a burning desire to give the maximum by performing a pose, carrying the aspirant beyond self-imposed limitations, which are all too often determined by inertia. In the fire of Tapas the longing for the divine is already stirring.

Svadhyaya: Through devotion to practise the practitioner learns to know the various dimensions of her´s/his own being. The way we do the poses reflects our mode of living in the world, including our attitude towards the divine source of the universe.

This leads us to Isvarapranidhana which only very few are able to realize in Asana. To master it means to be able to transform the pose into an act of surrender to God. This does not mean that while holding the poses prayers should be spoken in a loud or low voice. Rather, the Asana itself becomes a prayer, taken as a gift from God. In thankfulness the giver and his gift as such are present for the recipient. In case of the Asanas gratitude is realized through complete involvement in the pose, doing it with the utmost attention and precision. “Doing Asana is a grace from God. Take it or He will walk away.” [33]

5.3 Pranayama in Asana

In “The Tree of Yoga” and in his other books, too, Iyengar doesn´t say very much about Pranayama in Asana.[34] He stresses that in doing a posture we can extend the body fully only if we synchronize the breathing with the movement. He considers holding the breath in the Asana bad because it stiffens the body. Those comparatively unpractised are especially advised to go into the poses with an exhalation. [35]

In general, it may be added that a pose can only be felt fully if it is pervaded with relaxed breathing. Paying attention to the tension, relaxation and expansion connected with breathing plays an essential role in deepening the Asanas towards meditation. Moreover, the so-called postural-prana mentioned below is a phenomenon which is supposed to occur only in connection with sensitive breath flowing through the entire body.

5.4 Pratyahara in Asana

Pratyahara is mostly translated as “withdrawal of the senses from the world”, which is an easily misleading phrase. It doesn´t mean an elimination, a deafening or any other kind of reduction of the senses. Rather it is their soothing. It is a calmness that manifests itself not by restraining the senses but rather by removing restraints, in the sense of William Blake´s aphorism: “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.”

The cleansing of the doors of perception called Pratyahara entails a change of attitude towards that which is given through the senses. It is not our senses that need to be held back but we ourselves, since we block the senses with our self-centred possessive armour. The more we free ourself from this armour the more our senses are free not only to turn towards the outer world but also to turn inwards towards their source, which is hidden in darkness and silence.

In this sense Iyengar describes Pratyahara as release from the unsatisfactory cycle of compulsively seeking pleasures, which always is connected with fearful avoidance of uncomfortable situations. “Detachment from the affairs of the world and attachment towards the soul is Pratyahara.” [36]

In the exercise of Asana, Pratyahara happens when muscles and joints get into their correct positions: “…, when the muscles and joints are rested in their positions, the body, senses and mind lose their identities and consciousness shines in its purity. This is the meaning of pratyahara.” [37]

Further aspects of Pratyahara in Asana are a receptive, quiet condition of the head while in the posture; the integration of the eyes into the sensation of the whole body; and the awareness of the back of the body.[38] If these characteristics are present, inspite of the effort of maintaining the pose, a calm, listening and open attitude is achieved, which Iyengar calls humility. [39]

5.5 Dharana in Asana

“What are you focusing on? You are

trying to perfect the pose, but from

where to where? That is where things

become difficult.” [40]

Dharana is generally translated as concentration. It is derived from the root dhri: to carry, to bear, to hold (cf. dhara: the one who bears = the earth; dharanam: prop, support, pillar, stay, hold).[41] The word has been used in the Yoga tradition from ancient times. For example Katha Upanisad 6.11 speaks of indriyadharana, the holding (together) of the senses. In Yoga Sutra III, 1 Patanjali defines it as “binding the mind to a place” [42]

Dharana is more than simple concentration in the sense of stupidly staring at a certain point. It is an accurate care which heeds that neither the thing which is held by one´s attention nor the self of the one who holds it is lost. A story told by Somadeva in his Katha-Sarit-Sagara illustrates very well how Dharana implies dedication of the whole person: “Vitastadatta was a merchant who had converted from Hinduism to Buddhism. His son, in utter disdain, persisted in calling him immoral and irreligious. Failing to correct his son´s obnoxious behaviour, Vitastadatta brought the matter before the king. The king promptly ordered the boy´s execution at the end of a period of two months, entrusting him to his father`s custody until then. Brooding on his fate, the lad could neither eat nor sleep. At the appointed time he was again brought to the royal palace. Seeing his terror, the king pointed out to him that all beings are afraid of death as he was; therefore, what higher aspiration could there be than practising the Buddhist virtue of nonharming at all times, including showing respect to one`s elders.

The boy, by now deeply repentant, desired to be put on the path to right knowledge. Recognizing his sincerity, the king decided to initiate him by means of a test. He had a vessel brought to him, filled with oil to the brim, and ordered the lad to carry it around the city without spilling a drop, or else he would be executed on the spot. Glad of his chance to win his life, the boy was determined to succeed. Undaunted, he looked neither left nor right, thinking only of the vessel in his hands. He returned at last to the king without having spilled a drop. Knowing that a festival was going on in the city, the king inquired whether the boy had seen anyone at all in the streets. The boy replied that he had neither heard nor seen anyone. The king seemed pleased and admonished him to pursue the supreme goal of liberation with the same single mindedness and passion.” [43]

The story shows what Dharana in Yoga should be: Being glad of the chance to win one´s life and liberation, taking this chance with total attention on what is necessary to gain them.

In practising Asana according to Iyengar´s method, the specific posture becomes the place of meditation. What is Dharana directed toward in the pose? Iyengar says: “Dharana is concentration on a point. Dhyana is concentration from that point without losing the source: ´Can I attend the rest of the body?´”[44] Here it is said that Dharana is directed to certain points of the body which Iyengar calls sources. What kind of points are they and why are they called sources? “If you know the source of each and every asana,” he says, “then you are very nearer the truth. Otherwise it is just a branch moving.”[45] From this it follows that the sources of the Asana are those places of the body from which the truth of the pose, i.e. that which it truly is, its nature, can be understood and brought into appearance. Therefore Iyengar sometimes also calls the source the “brain” of the Asana, the brain being the organ of orientation, insight and reflected action.

Through the “brain” or “source” the position can be built up with intelligence and held according to its nature. Every source gives birth not to a part but to the whole of whatever emanates from it. So does the source of the Asana. It opens the posture as a whole. If the Asana doesn´t spring from the sources, it doesn´t become fully revealed in its unity. Instead, only parts are moved, in an isolated way: “It is just a branch moving”.

Where are these sources? “Whatever pose you do, that which is in contact with the ground or nearest the ground is the brain.”[46] Just as a building can only be erected on a solid foundation, being rooted in the ground is decisive for the various poses. The entire Asana springs from those points through which by breathing and with the weight of our body we unite ourselves with the supporting ground that gives us stability and the firm base to bring ourselves upright or to relax like in Savasana.

Other important sources of the postures are – and this may be surprising at first – the weak points, where nothing happens. Only by turning to those areas and waking them up the Asana can be experienced fundamentally, and that means in its entirety. “Once you know the portions that do not work, that becomes the brain for the pose, the source for action.” [47]

The hint at portions that don`t work is important, because by the very attention given to certain points, the inevitable danger of forgetting the others exists. This may have painful consequences: “You can lose the benefits of what you are doing because of focusing too much partial attention on trying to perfect the pose. … In concentration, you are likely to forget some parts of the body as you focus your attention on other parts. That is why you get pain in certain parts of the body. It is because the unattended muscles lose their power and are dropped. But you will not know that you are dropping them, because they are precisely the muscles in which you have momentarily lost your awareness.”

In order to avoid the dilemma that Iyengar speaks of here it is necessary to develop an attitude of concentration on those parts that were neglected and therefore are on the edges of our field of awareness. [48]

One has to expand the attention from the area that has been particularly extended over the whole body without losing the openness and stretch in the extended part. In doing this, Dharana already merges into Dhyana.

5.6 Analysis of the transition from Dharana to Dhyana in Asana

The role of extension, postural prana, body-scheme and structural analogies According to the German Indologist J-W. Hauer Dhyana is a compound of dhi: to put, to place and -a: near, up, on. If this is correct then Dhyana originally is a verbal noun meaning “the placing near”, which can be understood as the gradual narrowing of the distance between the one who is dedicating himself to something in Dharana and that to which he is devoting himself. The closeness of both becomes manifest when the onepointedness (ekagrata) of Dharana transforms itself into a steadily flowing stream of attention (ekatanata) connecting the two. [49]

Whereas in Dharana the attention still shifts between different aspects of the place which is contemplated, in Dhyana the place is perceived in its wholeness, by itself and in relation to itself. This is well illustrated by the commentary on the Yoga-Sutras which is ascribed to Sankara. It is said there, that someone who practises Dharana whilst contemplating the sun still notices various attributes of the sun, e.g. its being disc-shaped or its brilliance. In Dhyana, however, the continous stream of attention is not directed to the sun as being disc-shaped, brilliant, etc. but to the sun as sun and nothing but that. All the different aspects of the sun are integrated in one single perception of the sun in its wholeness. [50]

As far as the practise of Asana is concerned, the transition from Dharana to Dhyana means the development of awareness of the whole pose which transcends the concentration on different points and details. At the end of the last section I already pointed out that this transition is of great practical importance and therefore I want to dwell a little longer on the question of how this change is possible.

The wholeness of our bodily existence in a certain pose is always already there before we start to look at the manifold details. We don`t have to compose completely separated parts of our body and body-awareness. They originally exist in unity. But this unity and wholeness is more or less disturbed, dull and uprooted. So we have to work on the details to restore it from the sources.

As I already mentioned above a source is something which gives birth to something else that in its entirety springs from it. If you look at a mighty river it is almost incredible that it owes its existence to some little springs up there in the mountains. Although sources usually are small and inconspicous, they are the real centers of energy, more powerful than whatever is originated by them.

If source is the correct designation for the parts of the body upon which Dharana is to be practised in Asana, then these points must have the hidden power to emanate the correct pose in its entirety. How does this springing of the whole pose from the sources happen?

It doesn´t happen just by itself without the practitioner´s endeavour. Dharana, fixing the attention upon the sources of the pose, means more than just to feel specific points. In order to let the source be a source one must allow the position to spring from it. This happens if we extend ourselves from the sources into the various directions inherent in the pose. Extension is the key to Dhyana in Asana. It is a movement that is impossible without a continous flow of attention.[51] The moment we lose our attention the extended part is dropped and becomes dull. But the attention needed for extension is not in points. It is spreading throughout the whole extended area. The more the pose is unified in one single but multidimensional stretch the more the practitioner is aware of her´s/his bodily being as a whole, opening itself in every direction in which the pose is pointing.

In the stretch the multiplicity of sensitive points is increasingly united by a phenomenon aptly called postural prana by the Iyengar Yoga teacher Arthur Kilmurry: ” In a healthy, undistorted body, the muscular action follows certain patterns. In some areas, the muscles naturally tend to lift; in other areas, they tend to pull downward. When this natural action of the muscles is not inhibited, one can experience it as a circuit of energy flowing through along the inner lining of the skin. For lack of a better term, I refer to this wave of muscular energy as ´postural prana´.” [52]

With the concept of postural prana Kilmurry indicates a very important dimension of Asana. But I don´t think that he is right in explaining it materialistically as a mere result of muscular movement, or as subjective experience of muscular energy, because I would argue that the experience of prana is ontologically and epistemologically prior to the observation of the action of muscles and their physical energy. [53]

Anyway it´s true that the extension of the body in a correctly performed Asana is essentially not achieved by arbitrary muscular contractions but rather by placing the joints and bones into their correct positions and then following the directions of extension which inhere in the structure of the pose interacting with gravity.

When this is done, the contraction and release corresponding to the posture come by themselves and a flow is felt under the skin going in circles and running through the body, enlivening and invigorating the practitioner. The more correct the position, the clearer and simpler are the resulting circuits of prana along the arcs of extension and the easier an integral awareness of our bodily existence comes. The main traits of the pose are carved out and through this we as performers gain a well centered body-profile vibrant with life.

This experience is supported by the development of the so-called body-scheme which unfolds through practise. In psychology the body-scheme is defined as the sense of location and direction regarding ones own position and movement. This sense is absolutely necessary for orientation. Without the perception of where our arms and feet are, how long they are, in which direction they move and how far they can reach, our behaviour would be totally confused. The knowledge of these things is primarily not imparted by seeing but by the inner feeling of the body. Usually it´s limited within the narrow scope of daily life demands, but through Yoga we are able to widen it.

Being still unfamiliar with the poses in the beginning of training, one doesn´t know, for instance, which joint is stretched, or how far backward one´s leg can reach, etc.. Just as with learning to play the piano, because of our mistakes we initially have to turn our attention again and again to the detail movements and away from the sound of the whole. But the more the body-scheme develops, the more natural the pose becomes and the less it needs to be watched and corrected from outside. Then Asana becomes a way of being ourselves: No more “I am turning my knee to the right ” but “I am entirely in the pose”.

The widening of the body scheme is promoted by what might be called structural analogies and symmetries. The analoguos structure of the limbs and the different symmetries in the entire body are conducive to a personal presence in the pose as a whole and therefore it is helpful to pay attention to it in the practise of Asana. The experience of symmetry always implies an experience of the centre, the middle line. Centering ourselves in Asana leads our dismembered Ego to the remembrance of the Self, which is the aim of Dhyana.

5.7 Samadhi in Asana

“In some postures, we lose the sense

of duality and we live in peace, in a

joy we cannot express in words. And

even if we have to fight all our life to

feed this joy once more, it is worth

doing it.” [54]

Samadhi is a synonym of samadhana: sam = together; a = on; dha= abreviated dhi = to put, to place. It means both putting near and thereby putting together, joining together. That which by nature belongs to a unity is brought into this unity and becomes a whole. Patanjali defines samadhi as such: “The same (dhyana), when it comes to shine forth as the place alone, apparently empty of its own nature as knowledge, is called samadhi.” [55]

In Samadhi the meditator is not concerned with her/himself any more. The knowledge of the meditated place loses the structure of “I know this”. It becomes pure openness in which the place alone is present and the presence of the place is at the same time the awareness of the meditator. Both are in unity. What does this mean when an Asana is the place of meditation?

As soon as the resistance dissolves and nothing stands between the pose and the one doing it, the possibility of Samadhi is given. By divine grace the pose may become the presence of the self. “The mind should fade into the Vastness; the mind has to dissolve, and the self has to approach the subject”.[56] The body recedes from consciousness because the extension the practitioner has opened to goes beyond to the vastness of the universe and into the depth of its hidden origin. Staying firmly and quietly in this openness the depth of being shines forth and the joyful nearness of the divine can be felt in the cave of the heart.

As Geeta S. Iyengar says: “Asana means holding the body in a particular posture with the bhavana or thought that God is within. The Asana has to be held firm or ´sthira´ so as not to shake that divinity. Asana Jaya or conquest of Asana comes when effort ceases and stability sets in. The stability brings about a state of ´sukhata´ or bliss.”[57] This, however, is nothing else but Samadhi in Asana, for Geeta later describes Samadhi in the following way: “The meditator, the act of meditation, and the object meditated upon all three merge into one single vision of the entire cosmos. Supreme happiness, free from pleasure, pain and misery, is experienced.” [58]

[28] Light on Yoga Research Trust (Ed.), op. cit., p. 42.

[29] See B.K.S. Iyengar, The Tree of Yoga. Yoga Vrksa, op. cit., pp. 50-51.

[30] See above p. 13

[31] Ibid.

[32] See B.K.S. Iyengar, The Tree of Yoga. Yoga Vrksa, op. cit., pp. 52-53.

[33] B.K.S. Iyengar`s 60th Birthday Celebration Commitee (Ed.), op. cit., p. 503.

[34] See B.K.S. Iyengar, The Tree of Yoga. Yoga Vrksa, op. cit., pp. 52-53.

[35] Ibid. 57-58. The problem of breathing in the Asanas is also treated by Geeta S. Iyengar, loc. cit., 75-76.

[36] B.K.S. Iyengar, The Tree of Yoga.Yoga Vrksa, op.cit., p. 63.

[37] Ibid. p. 61.

[38] See Donna Holleman (Ed.), op. cit., 114 and 120.

[39] Ibid., p. 110.

[40] B.K.S. Iyengar, The Tree of Yoga. Yoga Vrksa, op. cit., p. 41.

[41] Concerning the etymology of Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi I follow J.W. Hauer, Der Yoga. Ein indischer Weg zum Selbst, Stuttgart, 1958, Kohlhammer Verlag, p. 319, 322 and 340-341.

[42] According to the translation of Trevor Leggett, op. cit., p. 282.

[43] G. Feuerstein, Yoga. The Technology of Ecstasy, Los Angeles, 1989, Crucible, p. 192.

[44] Dona Holleman (Ed.), op. cit., p. 125.

[45] Ibid., p.108.

[46] Ibid., p.131.

[47] Ibid., p.108.

[48] B.K.S. Iyengar, The Tree of Yoga. Yoga Vrksa, op. cit., pp. 41-42.

[49] See G. Feuerstein, op. cit., pp. 192-193.

[50] Cf. Trevor Leggett, op. cit., p. 283.

[51] “Extension is attention” Iyengar says in D. Holleman, op. cit., p. 111.

[52] Arthur Kilmurry, Sarvangasana, in: Yoga Journal, Sept./Oct. 1990, p. 33.

[53] To say it in terms of Indian philosophy: The pranamaya-kosa is pervading and enlivening the annamaya-kosa. This relation is not reversible.

[54] Noelle Perez-Christiaens, op. cit., p. 70.

[55] Yoga Sutra III, 3 translated by Trevor Leggett, op. cit., p. 283.

[56] Donna Holleman, op. cit., 118.

[57] Geeta S. Iyengar, op. cit., p. 25.

[58] Ibid. p. 29.

[Homepage of Iyengar Yoga Resources]

Você precisa fazer login para comentar.